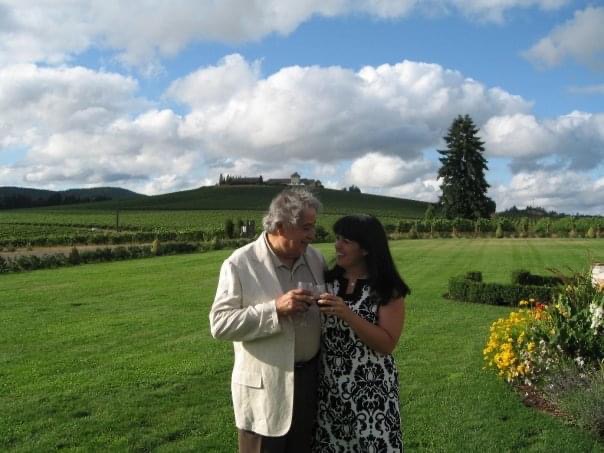

If you know me well, you know my father. Maybe you called him Mr. Chagollan, or Sam’s dad, or Pa (like I did)—but he would tell you just to call him Manny.

He likely sat across from you at my dinner table, or tried to teach you how to swing dance at one of our parties, or bought you a drink and told you a story about what LA was really like back in the early 1950s.

He was so much a part of my life, so woven into my identity as a person, that I am not sure who I am now that he is not here anymore.

It’s now been four months since we lost him to COVID-19. At his virtual funeral service, I talked about how my Pa was my North Star. He was always so good at directions, like he had an inner GPS system that I could call on at any time, both literally and figuratively.

In the weeks after that service, I felt physically ill. I had a bout of vertigo, where if I turned too quickly to one side or the other, the horizon line would start bouncing and my sense of balance was completely gone. As if I had actually lost my center.

Then the wildfires started, and that enormous cloud of smoke drifted over this part of the world and just stayed there. Our usual coastal breezes couldn’t push it out. Waking up to dark skies and and orange sun for 6 days in a row kept me even gloomier. The headaches started. And the grief settled in.

Of course I have been affected by death before. I have lost friends and teachers, grandmothers and classmates, and most tragically, my beloved mother-in-law.

I remember when my Granny died, more than 20 years ago now. She and I were so close when I was a kid. If I try hard enough, I can still remember the nappy feel of her favorite blue cardigan sweater—the one with the brass buttons and the roomy front pockets. I can smell her lilac perfume, and the way her kitchen had a permanent, lingering aroma of freshly baked biscuits and fried onions.

She taught me how to drive, how to bake a flaky pie crust, and how to set a beautiful table. She had shamrock sheets on her bed, and her tiny mobile home was stuffed to the brim with knickknacks and Roger Whittaker records.

I loved her very, very much. And yet when she died, I didn’t feel a sense of overwhelming grief. She was what, 92? She had been sick before. My mom insisted I see her in hospice. I reluctantly agreed. Her eyes were closed, and I don’t think she even knew I was there. The only sound in the room was her rattling breath.

I would have rather kept the other, sweeter memories of her closer. And though I missed her when she was gone, I didn’t feel the same gaping grief that my mother did. I loved her, and she was gone.

With my dad though, it’s different. I know he’s gone—I was there when he died. But it’s like my mind doesn’t believe my brain. Like walking through the brand-new Whole Foods near his house that carries the kind of almond milk he liked. I even pulled out my phone as I walked out to my car to call him and let him know. Lists of random things I want to tell him follow me around like ghosts. We used to talk or text at least every few days. Now I find myself saving things up to tell him next time we talk until I realize—ah, that’s right. There will be no next time.

Normally, I am the kind of person who always has a million different things going at any given moment. I’m a born multi-tasker, or jack of all trades (master of none), depending on how you look at it.

Before this pandemic, I was doing all the things. Teaching yoga and meditation, six classes a week. Freelance writing for some corporate contracts, writing two interviews a month for a digital magazine, and taking on book and other freelance projects on the side. Plus taking care of my parents’ medical and financial affairs, volunteering when I could, trying to squeeze in time for friends and exercise, and oh yes, meditating daily and maybe doing some art sometimes or cleaning the kitchen.

As the pandemic began, of course things started falling away. And I welcomed it. I realized how good it felt to have a simplified schedule. How much more breathing room there was once the hustle was gone.

And then more things, more jobs, more tasks disappeared too. “This is great,” I told myself. The Universe is making it easy for me to finally rest.

And then my Pa died. And my body shut down. And I literally had no choice but to be still.

Lately I am prone to spontaneous weeping. As if something within has sprung a slow leak that I am unable to plug. In bed when I first wake up. Hearing a song he loved, or noticing that so many TV episodes and movies involve someone losing their father tragically. Reading the news about the never-ending spread of COVID.

I no longer find solace in yoga, the place I once went for soothing all of my pains. I’m not even teaching anymore. Now my only physical comfort is either in running, walking or cycling until I am exhausted. Or the opposite—total immobilization. I lay inert on the couch under my weighted blanket for hours at a time, binge-watching true crime and social justice documentaries.

I am certainly searching for justice in my own loss. For reason, for meaning. I can’t seem to reconcile the gap.

Yes, he was 89. I knew the end was coming. I just wasn’t ready. But I guess we never are.

I feel like a ship without a sail. Or maybe just without a wind. He was so much a part of me, so ingrained, that I rarely had to ask for his advice or direction anymore. He had already taught me so well. I knew he would agree with my choices, and support my decisions, would back me up no matter what.

He was always so sure I would be okay. More sure than I was.

But now that certainty has vanished along with him. Maybe it’s the quarantine, or the loss of work that has resulted in all the free time I so longed for before this. But I just don’t know what comes next. I don’t know what to do with myself.

Is this what grief feels like? Like the person you love has been taken out of every scene? I’m reminded of the opening titles of the TV show The Leftovers, where the empty silhouettes of those who are gone are like cookie cutter cutouts in every scene.

So I go on my walks. Sometimes just a mile or two, down by the Santa Ana river trail by my house. Once I took a wrong turn and went for 8 miles. I came back dehydrated and limping, but I relished the pain. Another time I barely broke a sweat, but wept for the entire walk. I’m sure everyone who passed me on that tearful walk feared for my sanity.

Silently, I asked him for help. I told him how sad I was, how much I loved him, how I didn’t know what to do next. I asked him for a sign. Then I looked up, through my tears, and saw a huge bird—maybe a hawk, maybe a vulture—gliding on the late autumn breeze above me. He crossed above and in front, swooped around behind me, and circled again. Just floating, stretching his wings and seemingly gazing down on me. He followed me for a half a mile. Circling back and around again.

There you are, I thought. You’re still here after all.

What would he do with this grief? His own father died so young, at 56, when my dad was just 27. I think that must be part of what drove his joyful curiosity, his love of family gatherings, and his infamous tall tales. He wanted to soak it all up.

Maybe that is what he is trying to tell me, flying above and riding the wind. You just keep going. You live the most out of life. You love your family, you keep going, exploring, and learning. You catch the wind and let it carry you to the next place.

I think he would say, “That’s how life is, chula. Sometimes it’s hard, but sometimes it’s a lot of fun too.”

So I’ll keep walking, listening to the playlists with all the music he loved, leaning on my friends and my partner, and trusting that he taught me well enough to do this without him. Someday soon, this pandemic will dwindle, and we will have hugs from friends again, I can go visit my mom again, can host dinner parties and classes and go on vacations. I’ll catch the wind and let it take me somewhere new.